KRUSZYNIANY, Poland, Might 27 (IPS) – Dzenneta Bogdanowicz by no means imagined she would witness the development of a wall in the midst of nowhere, simply two kilometres from her entrance door.

“It’s proper there, so shut. And naturally, it’s dangerous for enterprise,” the 60-year-old Polish hotelier tells IPS exterior the wood guesthouse and restaurant she runs in Kruszyniany. It’s a village of 200 inhabitants 250 kilometres northeast of Warsaw, within the Podlasie area.

Though it is often called the “Polish Amazonia” for its wetlands and plush vegetation, Podlasie’s border with Belarus locations it on the coronary heart of Europe’s main geopolitical fault line.

In August 2021, Belarus started channelling a stream of migrants —principally from the Center East and North Africa— towards the borders of Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania.

For months, Minsk expedited the issuance of short-term visas. Many migrants flew to Minsk after paying between $3,000 and $6,000 to intermediaries who promised them entry into the European Union.

From there, they had been escorted to the Polish border, the place, in keeping with reviews, Belarusian troopers helped some climb the fence between the 2 nations.

The EU and impartial observers described it as a part of a “hybrid conflict” aimed toward destabilising neighbouring nations, in retaliation for sanctions imposed after Belarus’s controversial 2020 elections. Aleksandr Lukashenko was re-elected —as occurred in January 2025— having held the presidency since 1994.

In response, Warsaw began erecting a six-metre-high metal barrier alongside its 400km border with Belarus. Thus far, greater than 200 kilometres of bodily and technological boundaries have already been deployed.

The closely forested area was declared a restricted zone. Non-residents had been barred, and Bogdanowicz, like most in Kruszyniany, was unable to work for 10 months.

The federal government insists the wall has helped curb unlawful border crossings. Nonetheless, authorities cite one border guard killed and 13 injured—allegedly by migrants—between 2021 and early 2025.

However humanitarian teams inform a darker story.

In keeping with NGOs, not less than 87 folks have died within the area since 2021, and greater than 300 are lacking.

The continued instability has taken a toll on the tourism sector, one which many locals depend on for his or her livelihoods. For Bogdanowicz, nonetheless, it’s about excess of simply economics.

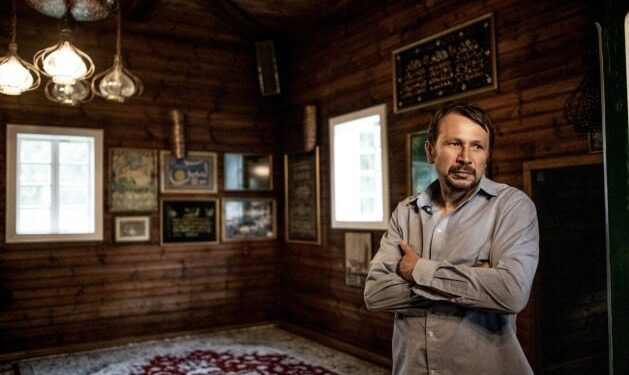

The wood advanced she constructed along with her husband almost twenty years in the past provides greater than rooms and meals. It additionally homes a cultural centre and a small museum, residence to centuries-old Qurans, conventional clothes sewn by great-great-grandmothers, and ancestral farming instruments.

“It was by no means about cash for us. We’re Lipka Tatars, and that is the guts of our neighborhood in Poland,” she says.

The Tatars settled within the area within the 14th century, rewarded with land and noble titles after combating alongside the Polish military. By the seventeenth century, they’d established themselves in Podlasie.

“Lipka” comes from the outdated identify for Lithuania within the language of the Crimean Tatars, with whom this predominantly Muslim neighborhood shares a typical ancestry.

In the present day, the wood mosque in Kruszyniany—constructed by Jewish architects 200 years in the past—nonetheless stands as a uncommon image of Europe’s oldest practising Muslim communities.

However that legacy now hangs within the stability.

Below the shadow of what some name a brand new Iron Curtain, the Tatars of Podlasie face isolation and financial decline. Tourism has slowed to a trickle. Census knowledge exhibits the inhabitants shrinking.

“There was once about 5,000 Tatars in Poland,” Bogdanowicz says. “However by the final census in 2011, we had been right down to fewer than 2,000. The concern, the restrictions, the curfews and lockdowns… It’s taken an enormous toll.”

Pressure and Confusion

A 2024 report by Human Rights Watch documented what it described as “a constant sample of abuse” by Polish border officers, together with illegal pushbacks, beatings with batons, pepper spray use, and destruction of migrants’ telephones.

Some had been reportedly detained a number of kilometres inside Poland, then pressured again into Belarus with out due course of. Human rights commissioners in each Poland and the EU have raised considerations in regards to the wall’s influence on press freedom and humanitarian entry.

Environmentalists, too, warn of irreversible injury to fragile ecosystems just like the UNESCO-listed Bia?owie?a Forest.

“What’s taking place in Podlasie stems from extraordinarily ineffective and unethical methods of dealing with migration,” stated Anna Alboth, chatting with IPS by telephone from Warsaw.

Alboth is a journalist and researcher with the Minority Rights Group, a UK organisation that works with ethnic and spiritual minorities.

“The Tatars have developed and preserved their very own cultural and spiritual traditions. They even served as a army caste for hundreds of years, a legacy that continues to be evident to this present day. Many nonetheless serve within the military or as border guards,” Alboth defined.

Nonetheless, the researcher additionally pointed to a “notably weak neighborhood” resulting from their small numbers. “It´s vital the Tartars stay concentrated of their territory to protect their id, however that’s changing into more and more troublesome,” she warned.

In response to questions forwarded by IPS, Poland’s Ministry of the Inside and Administration burdened the necessity to “defend nationwide safety towards the instrumental use of migration by the Russian and Belarusian regimes.”

Warsaw described it as “a part of a method aimed toward destabilising inside affairs in neighbouring nations and the European Union as a complete.”

Concerning the Human Rights Watch report documenting severe human rights violations by Polish border guards, the ministry said that the NGO’s investigators had been “unable to independently confirm the instances described.”

Officers declined to touch upon considerations associated to depopulation brought on by the disaster and the dangers to the way forward for the Tatar neighborhood.

With nationwide authorities staying quiet, Podlasie’s regional authorities stepped in final April with an area voucher scheme, providing 400 zlotys (round $105) to encourage tourism within the space’s lodgings and guesthouses.

However for some, the gesture feels too little, too late.

A Shared Graveyard

The highway from Kruszyniany to the Tatar village of Bohoniki winds by secondary routes and marshland. Many turn-offs eastwards now finish abruptly towards the metal wall.

Even figuring out whether or not you’ve entered the exclusion zone is troublesome. There are a couple of indicators, however frequent patrols.

In Bohoniki, the crimson wood mosque with its single black dome remains to be simple to identify. However guests are scarce. “Exterior summer season, hardly anybody comes anymore,” blurts Miroslava Lisoszuka, an area farmer who guides the few vacationers that trickle in.

She blames the confusion over border restrictions and lingering concern from the deadly assault on a border guard in 2024.

The disaster has even reached Bohoniki’s cemetery. Enclosed by stone partitions for over 200 years, the two-hectare web site on the village outskirts is the biggest Muslim burial floor in Poland.

On the farthest edge are ten easy graves. Amongst them lie a child, an unidentified grownup, and different migrants who perished within the forests. Every now and then, an area farmer or a border guard stumbles upon human stays within the mud.

© Inter Press Service (2025) — All Rights Reserved. Authentic supply: Inter Press Service