Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBC

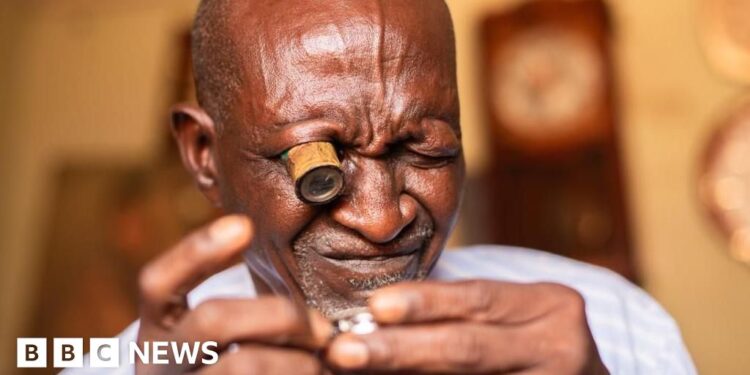

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBCTicking is the predominant sound inside Bala Muhammad’s tiny watch-repair store, tucked away on a bustling avenue within the northern Nigerian metropolis of Kaduna.

It is sort of a time capsule from a special period with quite a few clocks hanging on the wall and small tables on the entrance filled with his instruments and watches in varied states of restore.

His store is on one in all Kaduna’s busiest purchasing streets – sandwiched between constructing materials suppliers.

Till a couple of years in the past, he had a gentle stream of shoppers dropping by to get their watches fastened or get a brand new battery fitted.

“There have been occasions I get greater than 100 wristwatch-repair jobs in a day,” the 68-year-old, popularly generally known as Baba Bala, informed the BBC.

However he worries that his abilities – taught to him and his brother by their father – will die out.

“Some days there are zero prospects,” he says, blaming folks utilizing their cell phones to examine the time for the decline in his commerce.

“Telephones and know-how have taken away the one job I do know and it makes me very unhappy.”

However for greater than 50 years, the growth in watches allowed the household to make a great dwelling.

“I constructed my home and educated my youngsters all from the proceeds of wristwatch repairing,” he says.

His father would journey throughout West Africa for six months at a time – from Senegal to Sierra Leone – fixing timepieces.

At one stage Baba Bala was based mostly within the capital, Abuja, the place lots of the nation’s elite dwell – and he made a great dwelling tending to the watches of the rich.

He reckons his greatest prospects have been prime officers of the state-owned oil agency Nigerian Nationwide Petroleum Firm (NNPC).

Some had Rolexes – these can range wildly in worth however a median one prices round $10,000 (£8,000).

He says they’re lovely – and encapsulate his love for all watches from Switzerland. He himself owns a Longines, one other prestigious Swiss model, which he solely removes when he sleeps.

“If I step out of my home and I forgot it, I’ve to return for it. I can’t be with out it – that’s how vital it’s to me.”

At his store, he retains a lovely huge framed photograph of his father, Abdullahi Bala Isah, taken as he appeared up from his work bench a couple of years earlier than his loss of life in 1988.

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBC

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBCIsah was a famend horologist and his contacts in Freetown and Dakar would name him to make a journey after they had sufficient watches for him to are likely to.

He would additionally make common visits to Ibadan, a metropolis within the south-west of Nigeria – a literary hub and residential to the nation’s first college.

Baba Bala says no-one within the household is aware of the place his father learnt his experience – however it might have been on the time of British colonial rule.

He himself was born 4 years earlier than Nigeria’s independence in 1960.

“My father was a well-liked wristwatch repairer and his talent took him to many locations. He taught me after I was younger and I’m proud to have adopted his footsteps.”

Baba Bala began taking a detailed curiosity in understanding the intricacies of what the wheels and levers inside a watch do when he was 10 – and was delighted to find that as he acquired older it turned a great supply of pocket cash.

“When my fellow college students have been broke in secondary college, I had cash to spend on the time as a result of I used to be already repairing wristwatches.”

He remembers his talent even impressed one in all his lecturers: “He had points with a few of his wristwatches and had taken them to a number of locations and so they could not do them. When he was informed about me I used to be capable of repair all three of the watches by subsequent day.”

At one level, watches have been seen as vital as garments in Nigeria and many individuals felt misplaced with out one.

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBC

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBCKaduna used to have a devoted space the place many watch-sellers and repairers arrange their companies.

“The place has been demolished and is now empty,” say Baba Bala mournfully, including that almost all of his colleagues are both useless or have given up on the enterprise.

A kind of who admitted defeat was Isa Sani.

“Going to my restore store every day meant sitting down and getting no work – that is why I made a decision to cease getting into 2019,” the 65-year-old informed the BBC.

“I’ve land and my youngsters assist me to farm on it – that’s how I’m able to get by nowadays.”

He laments: “I do not suppose wristwatches will ever make a comeback.”

The children working on the constructing provide outlets subsequent to Baba Bala agree.

Faisal Abdulkarim and Yusuf Yusha’u, each aged 18, have by no means owned watches as they’ve by no means seen a necessity for them.

“I can examine the time on my telephone at any time when I wish to and it is all the time with me,” one stated.

Dr Umar Abdulmajid, a communications lecturer at Yusuf Maitama College in Kano, believes issues might change.

“Typical wristwatches are little question dying and with it jobs like wristwatch repairs too, however with the smartwatch I feel they may make a comeback.

“The very fact a smartwatch can do rather more than simply present you the time means it may proceed to draw folks.”

He suggests outdated watch-repairers learn to grapple with this new know-how: “For those who do not transfer with the occasions you get left behind.”

However Baba Bala, who returned from Abuja to Kaduna to arrange his store about 20 years in the past as he needed to be nearer his rising household, says this doesn’t curiosity him.

“That is what I really like doing, I contemplate myself a physician for sick wristwatches – plus I’m not getting any youthful.”

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBC

Ifiokabasi Ettang / BBCHis tight-knit household stay loyal to his career – his spouse and all his 5 youngsters put on watches and infrequently pop in to go to him on the store, the place a few of the timepieces on show are forgotten relics from outdated prospects.

“Some introduced them a few years in the past and did not return for them,” he says.

However Baba Bala refuses to surrender and nonetheless opens up every day – his eldest daughter, who runs a profitable garments boutique close by, helps him with payments when his enterprise is gradual.

With out a lot to maintain him busy – or the chatter and gossip of his prospects, Baba Bala says he now usually listens to his radio for firm, having fun with the Hausa language programmes on the BBC World Service.

Within the afternoon his youngest son, Al-Ameen, comes to go to after college – the one one in all his youngsters to indicate an curiosity in studying the artwork of watch-repairing. However he wouldn’t encourage him to take it up as a career.

He’s happy that the 12-year-old has informed him he needs to be a pilot – persevering with the household custom of seeing extra of the world.

In a cockpit, he can be confronted with many watch-like dials – not in contrast to his dad’s workshop.

You might also be fascinated with:

Getty Photographs/BBC

Getty Photographs/BBC